As the more geeky of patent law watchers know, the "abstract ideas" part of the Alice in Blunderland Supreme Court (SCOTUS 2014) decision finds its roots in Le Roy v. Tatham (1852).

One might assume that the Floundering Ancient SCOTeti Fathers of the 1852 version of SCOTUS were more reserved, scholarly and enlightened than our current crop of "New Romantics" like Clarence the Clown and 'Bacus Brain Breyer. But not so.

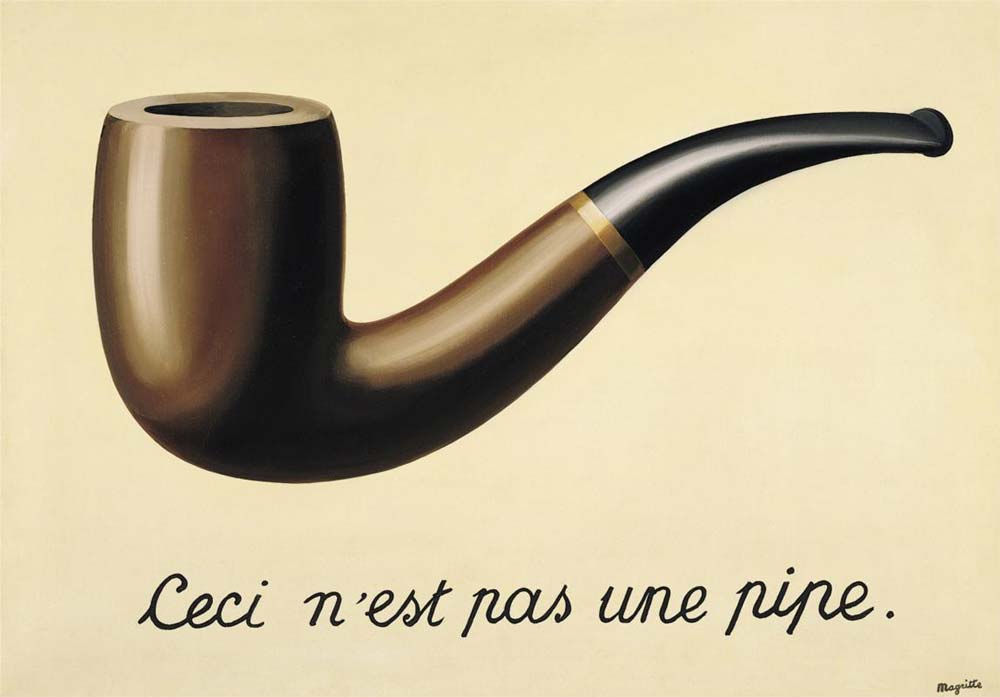

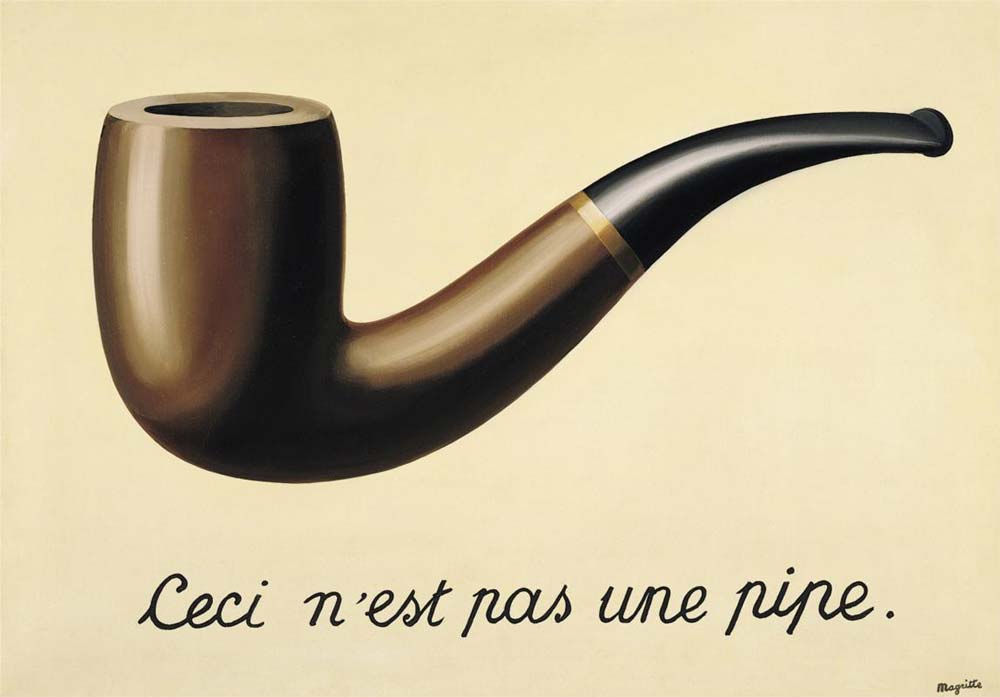

They too, at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution misunderstood science, technology and instead had mystical Illuminati beliefs in 'principles', symbolisms, confluence with Mother Nature and abstractions emanating from the shining eye on top of the pyramid of power. They write:

“A patent for leaden pipes would not be good, as it would be for an effect, and would, consequently, prohibit all other persons from using the same article, however manufactured. Leaden pipes are the same, the metal being in no respect different. Any difference in form and strength must arise from the mode of manufacturing the pipes. The new property in the metal claimed to have been discovered by the patentees, belongs to the process of manufacture, and not to the thing made.” --at 176

Clearly the SCOTeti of days yore did not, could not understand metallurgy or product by process. Nonetheless they considered themselves smarter than everyone else, even the inventor a.k.a. discoverer. How times have changed (not).

The 1852 SCOTeti go on to proclaim:

"The word principle is used by elementary writers on patent subjects, and sometimes in adjudications of courts, with such a want of precision in its application, as to mislead. It is admitted, that a principle is not patentable. A principle, in the abstract, is a fundamental truth; an original cause; a motive; these cannot be patented, as no one can claim in either of them an exclusive right. Nor can an exclusive right exist to a new power, should one be discovered in addition to those already known. Through the agency of machinery a new steam power may be said to have been generated. But no one can appropriate this power exclusively to himself, under the patent laws. The same may be said of electricity, and of any other power in nature, which is alike open to all, and may be applied to useful purposes by the use of machinery.

In all such cases, the processes used to extract, modify, and concentrate natural agencies, constitute the invention. The elements of the power exist; the invention is not in discovering them, but in applying them to useful objects. Whether the machinery used be novel, or consist of a new combination of parts known, the right of the inventor is secured against all who use the same mechanical power, or one that shall be substantially the same.

In all such cases, the processes used to extract, modify, and concentrate natural agencies, constitute the invention. The elements of the power exist; the invention is not in discovering them, but in applying them to useful objects. Whether the machinery used be novel, or consist of a new combination of parts known, the right of the inventor is secured against all who use the same mechanical power, or one that shall be substantially the same.

A patent is not good for an effect, or the result of a certain process, as that would prohibit all other persons from making the same thing by any means whatsoever. This, by creating monopolies, would discourage arts and manufactures, against the avowed policy of the patent laws.

A new property discovered in matter, when practically applied, in the construction of a useful article of commerce or manufacture, is patentable; but the process through which the new property is developed and applied, must be stated, with such precision as to enable an ordinary mechanic to construct and apply the necessary process. This is required by the patent laws of England and of the United States, in order that when the patent shall run out, the public may know how to profit by the invention. It is said, in the case of the Househill Company v. Neilson, Webster's Patent Cases, 683, "A patent will be good, though the subject of the patent consists in the discovery of a great, general, and most comprehensive principle in science or law of nature, if that principle is by the specification applied to any special purpose, so as thereby to effectuate a practical result and benefit not previously attained." In that case, Mr. Justice Clerk, in his charge to the jury, said, "the specification does not claim any thing as to the form, nature, shape, materials, numbers, or mathematical character of the vessel or vessels in which the air is to be heated, or as to the mode of heating such vessels," &c. The patent was for "the improved application of air to produce heat in fires, forges and furnaces, where bellows or other blowing apparatus are required."

A new property discovered in matter, when practically applied, in the construction of a useful article of commerce or manufacture, is patentable; but the process through which the new property is developed and applied, must be stated, with such precision as to enable an ordinary mechanic to construct and apply the necessary process. This is required by the patent laws of England and of the United States, in order that when the patent shall run out, the public may know how to profit by the invention. It is said, in the case of the Househill Company v. Neilson, Webster's Patent Cases, 683, "A patent will be good, though the subject of the patent consists in the discovery of a great, general, and most comprehensive principle in science or law of nature, if that principle is by the specification applied to any special purpose, so as thereby to effectuate a practical result and benefit not previously attained." In that case, Mr. Justice Clerk, in his charge to the jury, said, "the specification does not claim any thing as to the form, nature, shape, materials, numbers, or mathematical character of the vessel or vessels in which the air is to be heated, or as to the mode of heating such vessels," &c. The patent was for "the improved application of air to produce heat in fires, forges and furnaces, where bellows or other blowing apparatus are required."

In that case, although the machinery was not claimed as a part of the invention, the jury were instructed to inquire, "whether the specification was not such as to enable workmen of ordinary skill to make machinery or apparatus capable of producing the effect set forth in said letters-patent and specification." And, that in order to ascertain whether the defendants had infringed the patent, the jury should inquire whether they, "did by themselves or others, and in contravention of the privileges conferred by the said letters-patent, use machinery or apparatus substantially the same with the machinery or apparatus described in the plaintiffs' specification, and to the effect set forth in said letters-patent and specification." So it would seem that where a patent is obtained, without a claim to the invention of the machinery, through which a valuable result is produced, a precise specification is required; and the test of infringement is, whether the defendants have used substantially the same process to produce the same result.